Futuristic reflections…

“I can’t think of another film that has such a strong atmosphere. So melancholy, and the strangest feeling of nostalgia for a place and time that never was.” – Chris Cunningham on Blade Runner

It is arguably the greatest science fiction film of all-time, and even the most influential, and not just of the last thirty years. You can find its progeny in everything from Twelve Monkeys to Akira (despite the fact that both films were also based on other source material[s]) to even seemingly unrelated films; Christopher Nolan cited Blade Runner as a huge source of inspiration for Batman Begins. Blade Runner’s visual style, philosophical underpinnings, and melancholic, somber tone, have made a huge mark on art, anime, and music. In fact, so many directors and writers have been influenced by the movie that it seems that anybody trying to get anywhere in Hollywood needs to not only have seen this movie, but hold it near and dear to the heart.

Blade Runner’s influence is so significant that the great sci-fi cyberpunk writer William Gibson, upon viewing a mere twenty minutes of it, became convinced that his forthcoming book, Neuromancer, was done for, as the visual look he’d imagined for his novel was exactly like the visual look of the film. Would people think he was ripping the film off? Eventually, after many a rewrite, he finished it and Neuromancer became a landmark science fiction cyberpunk story. Blade Runner became a landmark science fiction film. Both works of fiction reached beyond the realms of sci-fi to others.

“Blade Runner came out while I was still writing Neuromancer. I was about a third of the way into the manuscript. When I saw (the first twenty minutes of) Blade Runner, I figured my unfinished first novel was sunk, done for. Everyone would assume I’d copped my visual texture from this astonishingly fine-looking film.” – William Gibson

Artists, amateurs and professionals alike, have conceptualized their love of the movie, and the genre of cyberpunk as a whole, through vast amounts of imagery. It is quite difficult to find a sci-fi film that proceeded Blade Runner that was not influenced by it in some shape or form (though, this could speak to how influential the cyberpunk genre is in its totality, or perhaps to how the world is becoming more and more cyberpunk everyday). Hell, maybe we hit that apex thirty years ago and are in decline now.

Released in 1982, the year of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Blade Runner, along with another now highly-regarded pic, The Thing, initially was given less regard. Its box office returns were disappointing and critics were more-or-less polarized at the time. Both Blade Runner and The Thing are now regarded by a great many as members of the sci-fi pantheon. In the opinions of this writer, both films were and are better than E.T. by a galactic magnitude.

The story for Blade Runner is actually very simple. It’s Los Angeles, 2019. Deckard (played inimitably by Harrison Ford, who manages to pull off both stoicism and charisma at the same time), a Blade Runner, must hunt down and retire (read: kill) a group of replicants (bioengineered beings that are virtually identical to humans) who have escaped to Earth. It really doesn’t get any simpler than that: officer hunts and kills superhumans. What Scott and his team do with the premise is ultimately what allows Blade Runner to transcend to the top of the genre.

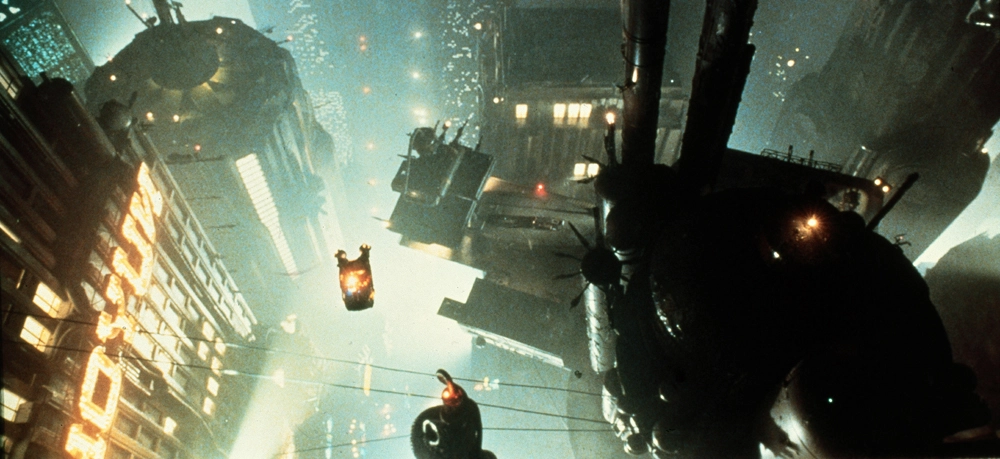

The film’s opening helps to establish both setting and atmosphere, as we are taken through a melancholic, near dream-like, journey across L.A., viewing glimpses of fire shooting off into the sky, and the vast arcologies of towering skyscrapers, all set to Vangelis’ haunting score. We get close-up shots of a human eye, hinting at the idea that what we see may not be real; it is the theme of perception that is prevalent in many science fiction works.

Perhaps the first and most noticeable aspect of Blade Runner is the breadth and scope of its visuals. Blade Runner goes beyond the beck-and-call of visual wonder, and literally immerses you into a world so unlike our own, and yet so similar. It’s one thing to take an already existing city, one that’s alive, and film it. It’s another to not only actually and literally build one from the ground up but to make it feel alive. In the majority of (sci-fi) films, when watching, one feels merely like an outsider looking into a fictional world. With Blade Runner, you actually feel like you are in their world, a part of it, experiencing it.

“It is no surprise at all that the style, the artefact [sic] designs and the scene designs have been copied… we labled [sic] our assembly style ‘retro-deco’ and added the additional label of ‘trash-chic’.” – Syd Mead

Blade Runner utilized “real world” settings (such as the Bradbury) alongside more futuristic elements.

Blade Runner is what we call “retrofitted”. It’s the prime example of a used future. In short: everything looks like it has a history. From the retro 1950s look (tech-noir) to the futuristic vision, the Los Angeles of 2019 is palpable precisely because it feels like everything has a past, from the cars, to the buildings, to the people. Think of a rundown Detroit, or of ancient ruins and older architectural designs coexisting with the new. This is opposed to pretty much every sci-fi film today which has a sleek and polished look via CGI. In Blade Runner, the atmosphere of the city, alone, just oozes out. You can feel the rain. You can smell the streets. It doesn’t have to be 3D for one to interact with it on a purely cerebral level.

“Modern Japan simply was cyberpunk.” – William Gibson

The L.A. of 2019 is also a highly-integrated mixture of cultures. The name ‘Hannibal Chew’, for instance, is an example of L.A.’s culture. It’s a city so congested with people that English coexists almost seamlessly with other languages. The so-called “American culture” and other cultures are slowly being intermixed into one product. For instance, Chiu is a homonym for Chew and, in my opinion, illustrates this idea of integration between American culture and Asian culture (specifically the East Asian [Japanese, Korean, Chinese] culture).

“The Chatsubo was a bar for professional expatriates; you could drink there for a week and never hear two words in Japanese.” – An excerpt from Neuromancer, Chapter 1

From the atmospheric scene in the animal market to basking in the sun’s rays at the top of the world, from Deckard’s apartment in the sky to Leon’s decrepit room, Blade Runner seamlessly combines the old and new, real and fake, together with a blend of cultures, into something now. What also helps is the normalcy of it all. No sun, a host of engineered animals (and humans), etc., and nobody bats an eye (so to speak). This is their world. The real 2019 is only seven years away. While it’s impossible to imagine the real L.A. looking like the one in the movie in seven years, it’s not impossible to believe it.

Blade Runner’s visual style is backed up by this dream-like atmosphere. I would go as far as to say that Blade Runner’s Los Angeles is not a created world. The world just is. In my mind, I don’t perceive of Los Angeles as a construction of the mind (though even a real city is constructed, over and over and over itself). I perceive it to be real (unsurprising, since perception is a theme in the movie). Of course, I am probably not the only one. People all over the net seem to be experiencing the same consensual consciousness; the vast amount of artwork, alone, inspired by the visuals of this movie litter the web, its creators and fans a undergoing what seems to a massive collective nostalgia for a place and time that never was.

“What I do is to think about why things are the way they are now, combine that awareness with how things were, are now and may be brought into reality. This defines the look of ‘future’ stuff. My scenarios are fanciful guesses that are the result of combining several layers of awareness and supposition.” – Syd Mead

Described as a visual futurist, Syd Mead was an instrumental force in the creation of the visionary and visually wondrous world of Blade Runner. His method is almost a summation of why the City of Los Angeles, 2019, in the movie, seems so real. The future L.A., like its present-day counterpart, is a city made up of a past, living in a present, and heading towards an unknown future. Indeed, his concept art alone could have generated the amount of enthusiastic futuristic art.

Concept art by Syd Mead.

The cityscapes depicted in Blade Runner and described in Neuromancer have become cyberpunk and, in a way, science fiction, commonplace. Not only does it lend itself to the genre’s posthuman, postmodern and postindustrial nature, but it also echoes its hyper-realistic nature. The film’s visual style is not the only factor which translates its philosophical undertones; additionally, such undertones are translated in force by its story, characters, dialogue, and overall themes.

Harrison Ford plays Rick Deckard, a solitary man who echoes the feelings of the countless alienated individuals living in our late capitalist society. In Deckard we find the archetypal cyberpunk character: alone, somber, depressed and rebellious. He is a post-Fordist, if you will; an exemplary postmodern and postindustrial character, a reflection of the depressive elements of such a cyberpunk society (high-tech, low-life). Ford’s Deckard is a representation of a man alienated by a system and city.

“You’re not cop, you’re little people!” – Bryant

He barely smiles, and even when he does he looks painfully-bored doing it. He seems eternally-disinterested with his work, seemingly going through merely motions, and living day-to-day in what seems to be existential ennui, and he never even has to say it. He is the socially-alienated loner of late capitalist, postmodernist, postindustrial society. His attitude characterized more of somberness and anomie than anything that feels truly productive. The most fascinating thing: he may not even be human himself.

“How can it not know what it is?” – Rick Deckard

What it means to be human: the classic cyberpunk (and, perhaps, sci-fi) question. Cyberpunk, and Blade Runner, effectively asks what it is to be human from the viewpoint of its central themes. How does the world’s high tech inform its humanity? What of its society; does it inform humanity, or does humanity inform it? How do ideas such as morality, mortality, time, and perception influence or inform humanity? What of the thing that makes us most ‘human’: memory? What does it mean to be human? Interestingly enough, this question is never explicitly asked in the film, and it is merely hinted at (though, in obvious ways).

“I don’t get it. What do they risk coming back to Earth for? That’s unusual. Why? What do they want out of the Tyrell Corporation?” – Rick Deckard

This idea of humanity is contrasted especially between Deckard and the replicants, principally Roy Batty (played by Rutger Hauer), but to an extent also Rachael (Sean Young). Deckard, supposedly human, shows little sign that he is; as noted before, he does not show a lot of emotion and he seems eternally-bored with his job (which is probably more a sign of obligation than anything else). Batty, on the other hand, a replicant, ironically seems so much more alive, despite the fact that, well, he’s not human (or is he?) and that he will be dead shortly.

“‘More human than human’ is our motto.” – Dr. Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel)

It is interesting to consider whether or not Deckard is human in this light. This is even truer when he is contrasted with Rachael. How interesting would it be for two artificially-created humanoids to actually make love? It is an action so… “human”; there is arguably nothing more beautiful than when two people in love make love. If they are both replicants, where did they develop such feelings from? Where did they learn such behavior? Is it simply the result of piecing together false memories and advanced learning? What does it mean to be human? Are you human if you love and make love like humans?

The film also presents the idea of a fundamental lack of control on the part of human beings, and that the world is constantly in flux. There is also the theme of perception which permeates the film. Few films have ever dwelled on this theme as well as or better than Blade Runner. All of these themes are connected in some way to the other. For instance, one can connect the themes of perception and change towards the idea of morality; are the replicants really “bad”? Where is the morality in eliminating those that seem to be as or more intelligent than humans, without prejudice?

The film has a sense and attitude of rebelliousness and/or antiauthoritarianism – stemming from its theme of lack of control – that is characteristic of many cyberpunk works. It is not as explicit as many of the others, but if you were to look closely, it is definitely there. Deckard, for instance, is shown at the beginning of the film to be a kind of upstart, a man who was apparently so rebellious that he is introduced as unemployed, and once again needed to do his job (technically, he “quit”, but we are not made aware of the exact nature of his departure). His very existence seems to be the filmmakers attempting to make a statement on the futility of a late capitalist culture.

“Revel in your time.” – Dr. Eldon Tyrell

But the attitude of rebellion is most present in the replicants. Seeming human beings who wish to defy their very nature and defy death itself. They seem alive in a world that seems existentially-dead. Their rebelliousness is not only against their very nature, but against the system itself. The illustration becomes obvious when Roy Batty murders their “father”, their designer, Dr. Eldon Tyrell; a primary symbol for authority, in general, in the film, not just as the “patriarch” of the replicants.

What is most interesting about this antiauthoritarian behavior is that it is not programmed, nor is it the purpose of the replicants. It seems to be a byproduct of their actions, not vice versa. The antiauthority attitude seems to stem from the total lack of control presented in the film. After all, these were bioengineered beings, lifeforms created for humanity’s use. That they could “override” or ascend beyond their own capabilities and develop a humanity that has the audience utterly confused between them and ‘real’ humans is an example of the illusion of control. As aforementioned: how do they know how humans act? It also speaks to themes of change and of perception (what is it to be human?).

The city depicted as Los Angeles 2019 is the result of a massive consensual memory, both the memory that created it, and the memory that lives in the audience’s mind, the nostalgia. Most things that require progression, such as history, economies, societies, ideas, and cities, are but the greatest of triumphs of collective human memory. Everything is built on something previous, things that preexist, and are the outcome of human memory. Memory ends up being one of the key themes in this film, and also relies on perception, change, and control to ask questions.

“We began to recognize in them a strange obsession. After all, they are emotionally inexperienced, with only a few years in which to store up the experiences which you and I take for granted. If we gift them with a past, we create a cushion or a pillow for their emotions, and consequently, we can control them better.” – Dr. Eldon Tyrell

The idea of memory is most explicitly explored in the replicant Rachael. Rachael sincerely believes herself to be human and, until it is revealed otherwise, the audience believes it, too. The reason she is so human is because of implanted memories. This seemingly makes her human. Memories, after all, are what separate human beings from each other (even similar experiences can be subjective); of course, with increased technology, one wonders if the idea of even memory has become stale. Such ideas of enlivened memories give way to Roy’s final speech, in which his own experiences are shared to Deckard and, by extension, the film’s audience; he is not just an engineered being, he is capable of retaining his past memories. Memory gives one his or her identity, and Roy is no exception. His own memories have allowed him to become the liveliest character of the movie. It is a bittersweet moment when he expresses to Deckard that all of his memories are about to be lost.

“All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” – Roy Batty

The theme of perception is made explicit in the symbolism of the eye; a close-up of the eye is seen several times at the beginning of the film. Note that it is not relegated to this symbol. There are obvious references to things not being what they seem: the subjectivity of memories and experiences, and even Deckard’s pursuit and search of the replicants (remember the apartment scene and the scene in which he analyzes the photograph) and, as a consequence, himself, are all facets of this theme of perception. Also take heed of the symbolism that occurs when Roy Batty crushes his “father’s” eyes.

“Chew, if only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes.” – Roy Batty

Identity, perception, memory, time, humanity, nostalgia, experience, posthumanism, politics, society, architecture, science, excitement; in this film, it was all there. And although it seems hardly fair to skimp over the details (I had planned on a few essays here and there), to talk about them all in too much depth would result in a disastrously-prolonged effort. The important thing of this film is that, thirty years later, it has earned, and continues to earn, the respect it so rightly deserved. Thirty years later, it has shown itself to be one of the most influential sci-fi films and continues to inspire both audiences and artists – amateurs and professionals alike – and had prescience unforeseen. But in many ways, the greatest praise can only come from your peers (writers, directors, artists, creators, etc.), who have done their fair share of criticizing and discussing the film. It may seem hypocritical of me to ostensibly appeal to authority, but I believe that often the best criticism and praise can be gauged from the peers who review your work and/or are influenced by it:

Tim Burton once said that, “So few great movie cities have been built. Metropolis and Blade Runner seem to be the accepted spectrum”; and once tried to shake Batman’s Gotham from the Blade Runner influence by stating: “If people say that Gotham City looks like Blade Runner, I’ll be furious!” (see Tim Burton Interviews, edited by Kristian Fraga, 23)

Stephen Spielberg said: “Minority Report is a different film. There’s darkness to it. There’s personal tragedy as well. But I think it’s a little more accessible. I thought Ridley [Scott, director of Blade Runner] painted a very bleak but brilliant vision of life on earth in a few years. It’s kind of acid rain and sushi. In fact, it’s coming true faster than most science fiction films come true. Blade Runner is almost upon us. It was ultranoir.”

Mamoru Oshii: “People tend to classify my movies as cyberpunk fictions but I personally don’t think they are. There are some films that I really enjoy such as Blade Runner, and they may have been helpful in shaping my movies to a certain degree. When you create a film dealing with humans and cyborgs, you have no choice but to refer back to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, as this movie is probably the foundation of movies with this theme. Whether I’m trying to re-appropriate his language or not may not apply to my movies, because my goal is to always make a new movie that nobody has ever seen before.”

Christopher Nolan: “I have always been a huge fan of Ridley Scott and certainly when I was a kid. Alien, Blade Runner just blew me away because they created these extraordinary worlds that were just completely immersive. I was also an enormous Stanley Kubrick fan for similar reasons.” The man compares Blade Runner (and Alien) to Kubrick (on a certain level, anyway).

Richard Linklater: “My opinions on previous Philip K. Dick adaptations are probably really similar to everybody else’s. I think we all rally around ‘Blade Runner’… It’s more in the film noir tradition to have a narrated voice – and you kind of need it to pull the elements together. It’s not cheesy or bad in any way. It’s classic. But I saw it in the theater at the time, too, so maybe it’s just special to me.”

Guillermo Del Toro: “Blade Runner is simply one of those cinematic drugs, that when I first saw it, I never saw the world the same way again.”

Mark Leckey: “The film that has had the greatest influence on me is Blade Runner (1982, directed by Ridley Scott). I love this film for the same reasons I love Roxy Music: they share a sense of yearning for the past and the future, for another place and another time, but it’s flattened out, so everything seems to occur at the same time in the same space. In Blade Runner you really feel that everything and everyone is piled on top of each other, mounting up like wreckage at the feet of the angel of history.”

The Wachowskis: “Blade Runner was a benchmark science fiction film, a masterpiece. Of course there’s influence. But we were like the only guys who liked that movie when we saw it, everyone else hated it.”

Zack Snyder: “I first saw Blade Runner when I was 16. It rocked my world. All those incredible images were burned into my psyche. It’s one of those movies you can’t help but quote, an involuntary reference source that will be recycled throughout cinema forever. It’s like a lesson from the master saying, ‘Go out into the world and do good.’”

Curtis Harrington (in 2004): “My favorite big commercial movie of the last twenty or twenty-five years is Blade Runner. I really love it and I’m so disappointed in the director. I don’t think he has any high ambitions, it’s not that, but he certainly hasn’t made anything close to Blade Runner since it was made…”

And so on… The list is endless, in addition to the countless films, art, anime, stories, etc., which were inspired, willingly or not, by involuntary submission or otherwise, by Blade Runner (and cyberpunk in general) speak volumes to the amount of influence the film has had. I predict that in another thirty years, this film will continue to resonate with artists and audiences alike.

Personal note: This was a review that I started a long time ago that I decided to finish [as best as I could, anyway] for, well, personal reasons. It is not the best writing I have ever done, but it is nonetheless here.

Related articles

- Blade Runner (randomfilmmusings.wordpress.com)

- Syd Mead Concept Artist (aggd.wordpress.com)

- Blade Runner article up on MovieVine.com (lukemassey.co.uk)

- Made On Earth and Blade Runner (geeknewscentral.com)

Excellent review! I love watching movies from past decades, because it allows me to compare them to movies from today, and see how things have changed. All the best in 2013!

Yeah. Or see how they’ve held up; whether they’ve rose in stature or have become forgotten. Of course, films are a product of their times; I love a lot of films because, for instance, they were so ’80s. But it’s always interesting to see which films have stood the test of time, and which haven’t.

There are only a few movies that I can sit through repeatedly without being bored. Most of them (with the exception of one) are from the 1980s.

“In the opinions of this writer, both films were and are better than E.T. by a galactic magnitude.” That is a very good point. I don’t even think of Blade Runner or The Thing as being as old as E.T., and they certainly have more relevance today than E.T. does. But in 1982, who knew?

Honestly, I wasn’t even around in 1982. But it’s always interesting to see which films didn’t fare so well at the time compared to the ones that did, and then see how it all turned out later. I’ve a few choice words to say about both Spielberg and E.T. (mostly negative) that I’ll save for another time. But I agree. Both Blade Runner and The Thing have risen considerably in stature, while E.T., well, hasn’t. In the grand scheme of things, you’re right: who knew? It will be interesting to see where the three stand another thirty years from now.

Pingback: Making Amends: Blade Runner (1982) | The Shadowzone·

Pingback: On Blade Runner | The Progressive Democrat·

“All those memories will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” – Roy Batty

Moments. It’s ‘moments’.

Nearly four years later, and this misquote has finally been surveyed. Now corrected.

Thanks.

I saw the Movie just when it came out. I was into SciFi. I was also a huge fan of Vangelis having listened to Albedo 0.39, Heaven & Hell. So just the opening scenes with the huge dark world of future LA, the extremely big buildings – like mountains – and the wonderfull voice of Vangelis blew me away. I have off course seen it qutie a few times after that and it does not seem dated at all. I guess that we will all find out what a great job Riddley Scott and co. did when they do a remake.